I recently spoke at the Agile In the City London conference. As well as watching a number of great presentations, I also was lucky enough to be able to give two presentations and I’ve shared the slides below.

I recently spoke at the Agile In the City London conference. As well as watching a number of great presentations, I also was lucky enough to be able to give two presentations and I’ve shared the slides below.

tl;dr No-one really likes performance reviews. But giving your team members good, actionable feedback and setting clear direction with them is very important. In my team we changed how we did performance reviews.

Note: This is the last post in a series on performance management and review. It’s worth reading the other three first:

As I mentioned in the last article, we ran the new process for four checkins, i.e. one cycle and then sought feedback from the team. They told us that:

So we now had some feedback to work with. Overall the experiment had been a success and was worth continuing with, albeit with some small changes. So what did we change?

When we rolled out the initial version of the improved process we wanted to keep things simple. This meant having a small number of different themed sessions (the Atlassian process has six different themes – we had used four of them). One thing that was missing was a session where the team member could just discuss anything that they wanted. This session became the Check In.

It’s a general catch up with no agenda. As with every themed session the team member also discusses how they think they have performed and gives themselves a feedback score, and the manager then gives the team member feedback and a score themselves. Any differences are then discussed, just like in any other session.

Team members are also encouraged to put any important agenda items to discuss into the checkin form beforehand so that the manager has time to prepare.

The session is targeted at 30 minutes only, as usual.

The second themed session that we introduced was 360 Perspective. Feedback had shown that team members would appreciate getting feedback from not only their manager but also their peers. The company performance management process mandated this should happen once per year.

Feedback is important but most people do not like or feel comfortable giving feedback. There’s multiple reasons for this:

The 360 Perspective session gives the opportunity for the team member to collect feedback prior to the session, add that to the form, and then discuss with their manager during the session. Managers are of course free to also collect feedback for discussion as well, but all feedback requests should be open and visible to all rather than anonymous.

In the future we hope to make feedback gathering and discussion a team activity.

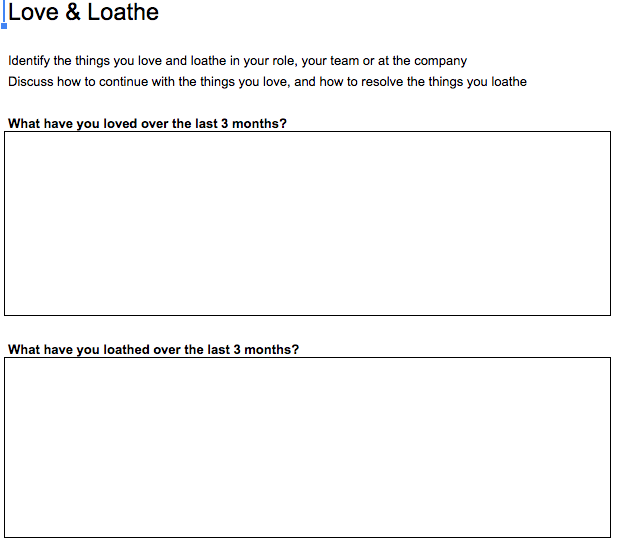

Our team members had also told us that they thought that some of the sessions were too similar. On further investigation this was because sessions that had similar themes (Love&Loathe and Removing Barriers for example) were too close together, resulting in similar topics being discussed in each. Since new themes were also being introduced then there was also the opportunity to change the timeline and space things out better to remove potential duplication and a perception that some or all of the process was not valuable enough.

The new timeline not only spreads things out better but it also aligns key activities such as 360 Perspective with the expectations of the yearly, company wide, performance management process. This enables both processes to effectively co-exist.

This was also a good opportunity to remind everyone of the need to make sessions short and punchy, therefore avoiding making the whole process too time consuming.

As well as introducing the new themes we also made changes to the form (get in touch if you want a copy). We added a clearer section for managers to leave feedback and the results of each session so that the form built up into a month by month record of achievement for each team member.

By doing so we enabled a very simple end of year discussion, as mandated by the companies yearly performance management process. A quick discussion to collate the month by month feedback, combined with feeding back the average of the monthly performance scores is all that is necessary. In order to set expectations as we go through the year then the form also now includes a predicted rating and graph of each team members progress.

So there’s no big performance review session that no-one looks forward to, no surprises for team member or manager at review time, and no concerns or fears about the outcome.

If you want to learn more about introducing a more regular and valuable performance feedback and review process then the links below are worth reading:

tl;dr No-one really likes performance reviews. But giving your team members good, actionable feedback and setting clear direction with them is very important. In my team we changed how we did performance reviews.

Note: This is the third post in a series on performance management and review. It’s worth reading the other two first:

In part two of the series I talked about how my team and I took the performance review and feedback system that is used at Atlassian and adapted it to suit our groups context. I talked about the themed ‘checkin’ sessions and how we got the whole group working to a common timeline for review and feedback, and the advantages that brought.

We what happened? How were the changes received and what was the feedback from the teams?

Once we were clear on our direction, we had agreed as a leadership team how we wanted the process to work and what themes we were going to use, then we prepared to sell our idea to the rest of the team. I strongly believe that one should not dictate changes that affect people’s career development or relationship with their manager, and so it was critical to us that the team members were bought into the ideas of the changes and our reasoning for proposing them.

We gathered the team together and explained the new process and how we felt it benefited them. I explained how I felt that the traditional process was sub-standard and could be improved. The key messages were this:

Feedback is better when it’s timely and so we want to start a process where that timely feedback enables higher quality discussions about you

As a group we agreed to run the process for one cycle and then review the results. If, after that, the teams were happy to continue then we would continue and if not then we would stop and revert back to the company-wide yearly cycle.

The issue with selling an idea to a group is that often, in private, people will express their reservations more freely. So it was key to ensure that managers then spent time with their team members and gave them the opportunity on a one-to-one basis to discuss the new process. This was also a good opportunity for managers to explain the process in more detail and seek additional buy-in.

The checkin sessions themselves are intended to be 30 minutes long in order to ensure that the process does not take too much time every month. It ensures that only the valuable things are discussed, and the sessions can be to the point and targeted at what matters. However, since this was a new process then we ensured that the first few checkin sessions ran to an hour so everyone could get the hang of it.

Since checkin sessions were short and punchy – although not literally 🙂 – then it was critical that everyone prepared for them. The checkin’s process works if the team member comes to the session having already prepared what they want to talk about. In order for them to be able to do that then we needed somewhere that they could document their thoughts.

Being an MVP then we did not want to spend much on supporting tooling (there is an excellent tool called Small Improvements which supports this sort of process) so instead we designed our own form. It’s simple and includes questions that the team member should answer in order to prepare for the session. The idea is that they fill in the relevant tab before each session, the manager can then review and prepare based upon the information they’ve entered, and then the checkin session itself can be focused on the discussion and actions from that discussion, rather than the actual ‘thinking’ time. It allows sessions to be targeted and valuable.

We designed our own form to support the process. If you’d like to see a copy then get in touch. We used the questions below to drive discussions:

Another advantage of using the form was that each team member built up a record of their year, what they had done, and how they had performed. This meant that when we did need to provide yearly feedback into the main company process then it was simply a matter of extracting the information we already had in each form. It was also great to encourage team members to look back through their forms to see what they had achieved throughout the year.

By meeting with our team members every month for themed, targeted performance and career management discussions then it also meant that we had a great opportunity to give them quantitive feedback. Like a lot of companies, we use a four point scale and at the end of each year every employee receives a performance review score which has an impact on salary and promotion – standard stuff in most companies. Once per year with no indication in-between how they are performing relative to that four point scale.

This seemed unfair so we adapted the checkins process to also include giving the team member feedback each more on how they had performed against the scale and why. This helped solve multiple complaints against a yearly system:

However, merely getting a feedback score from the manager still presents a surprise and it was important that the manager was able to have a meaningful two-way discussion about performance. In order to drive this we asked each team member to give themselves a score, on the same scale, before the session. This enabled the manager to then understand how the team member felt they had performed, and it encouraged the team member to think about their achievements during that month. The discussion, held towards the end of the checkin session, could then be focused on any differences between the manager and team members interpretations of their performance.

The first rounds went smoothly. One thing we learnt pretty quickly was that it took time to adapt to the process and so running the first couple of checkins for each team member as hour long rather than 30 minutes was definitely necessary. There was also some prompting required of some team members in order to get the forms filled in prior to the checkin session rather than during the session but this was to be expected given that the process was different and new.

People were surprisingly happy to provide a feedback score for themselves and by asking them to do so, we were able to make more meaningful and example based discussions on how they had performed.

As we had promised, we ran the process for four checkins, i.e. one cycle and then sought feedback from the team. Broadly speaking it looked like this:

We now had some feedback to work with. Overall the experiment had been a success and was worth continuing with, albeit with some small changes. Overall we had:

In the last article in this series I’ll explain what we did in order to improve the process to suit our context even better, and some of the key learnings we got from running the process over a longer time period.

tl;dr No-one really likes performance reviews. But giving your team members good, actionable feedback and setting clear direction with them is very important. In my team we changed how we did performance reviews.

Note: This is the second post in a series on performance management and review. If you haven’t read the first one on Improving Performance Reviews then I recommend you take a look at that first before reading on.

As I mentioned in the previous article, a cycle with yearly performance reviews doesn’t work. Objectives become irrelevant or forgotten, the business and team landscape changes, and people simply don’t get comfortable being a part of, or good at, something that only happens once or twice a year. As a result the traditional performance reviews and objective setting cycles that a lot of companies use end up becoming de-motivating for both team members and managers and are just something “to get out of the way” each year before moving onto “real work”.

It doesn’t have to be like this.

Both me and my management team were becoming frustrated by being part of a performance management process with yearly performance reviews that we felt was not enabling us to get the best out of our teams. We wanted to change things. But, as part of a large company with pre-existing people processes, we did not have the mandate, nor the time, to initiate company wide change. So what we did was driven by a need to make both a positive change for our teams and also to still fit within the existing yearly cycle that the company uses. An attempt at getting the best of both worlds. And to fly a little under the radar while we proved the concept.

Let’s not forget, as Grace Hopper once said – “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission”.

So we made some incremental changes which we feel has had a positive effect on our team’ member’s career development, their motivation and our motivation too.

When it comes to anything involving people then it pays to seek advice from as many different people and sources as possible. We looked at how a number of different companies were doing their performance management, companies ranging from those that did no formal sessions, to those that did a lot. There was one that really stood out – Atlassian. What Atlassian had done with performance management seemed like something that would fit with our thoughts on the types of changes we wanted to make.

I won’t explain why the Atlassian model is good in too much detail, because they have done a great job of that themselves. I suggest you read their posts which explain much more.

In short, what they had done was take the traditional model, split it into bite sized chunks, distribute these throughout the year and enable timely performance feedback. Exactly what we were looking for.

Now, it’s very easy to read blog post after blog post about other companies cultures and how awesome they are. I’ve seen it argued that a key measure that investors use when deciding which start-ups to invest in is the company culture, and so companies blog copiously about their perfect culture. Even if they aren’t exactly the whole truth. It’s always wise to treat these article with a pinch of salt and find somewhere else that has actually adopted similar changes. Fortunately we found that REED, a large UK based recruitment site had taken the Atlassian model and were using it day-to-day.

So we contacted REED and spent some time with their technology leadership team discussing how they had implemented the Atlassian model and what their experiences were. After those discussions we felt confident that the Atlassian model, while it would require some adaptations to suit our context, was usable, workable and something worth trying.

Given that we needed to work within the company performance management cycle and policy then we were able to take some parts of the Atlassian model but not all. The model overall splits into four different areas:

Unfortunately we had no control over the payment of bonuses, and the performance evaluations (a.k.a a yearly performance ‘score’) needed to be fed back every year. Changing this just for my group was not possible and even if we had been able to do so, it would have presented a very confusing view to the team members who are also part of a wider technology team not using our new process. There was also the danger that if we started to evaluate our teams differently then that could have impacted how they were evaluated in comparison with their peers outside of the team, with potentially negative consequences. So we focused on implementing a system with bite sized chunks of feedback and review, together with ‘scoring’ using the same four level system that was implemented across the company.

The Atlassian model uses six different themed sessions called Checkins to drive performance and career development conversations. These are held monthly, targeted at taking about 30 minutes each and the discussions are led by the team member. Everyone has the same checkin at some point within the same month.

For our initial MVP of the process we decided to use four of the themes:

It was very important to explain the different checkin themes to the team, set expectations on what the team member needed to do to prepare and what the intended outcome was of each session. That way we could explain the value that could be gained from each session. We prepared cards that each team member could use to understand more.

It was also important to ensure that it was clear to everyone when discussions needed to take place. By ensuring that everyone in the group (managers included) had the same themed checkin discussion each month then, as a leadership team, we were able to meet at the end of the month and identify any common themes that had arisen from discussions. For example, was there something that was blocking a lot of people? Could we allocate some budget or additional focus to doing more team building, changing a process, buying more equipment, etc that would benefit the team as a whole? Were there some stakeholders that multiple team members were having issues with connecting with? What was making the team members happy and therefore we should be doing more of?

By having a common dataset at the end of each month we were able to have far more meaningful and valuable conversations about change than we had been able to have before.

We used the timeline below to ensure a common focus across the team.

In the next article in this series I’ll explain what happened. How did we roll out the new process to the team? How did we continue to evaluate performance in-line with our new monthly process and the companies expectations, and how did we ensure a common approach to preparing and recording the output of each of the checkin discussions? How was the new process received by the team?

tl;dr No-one really likes performance reviews. But giving your team members good, actionable feedback and setting clear direction with them is very important. Yearly performance reviews don’t encourage this to happen.

Note: This is the first part in a multipart series of posts on performance management. In my team I changed how we do performance management. Future posts explain what changed and what happened as a result. This post sets the scene.

It’s fair to say that the traditional way of doing performance reviews is exactly that, traditional. Many companies work on a yearly cycle, with managers setting their people some objectives at the beginning of each year then reviewing them at the end. It’s likely that it’s been that way for ever. Sometimes if you are lucky then they’ll also be a mid year review.

I have a problem with this way of managing performance. We try to teach our teams to think in the present, to inspect and adapt their ways of working and the feature sets of products themselves, regularly and iteratively. Yet when it comes to the people we do the opposite. It doesn’t make sense.

I’ve seen the following problems with the yearly review cycle in a number of companies that I’ve worked in. The same concerns and feedback every time.

Firstly there’s a huge gap between when someone is set some objectives and when those objectives are reviewed. Objectives get forgotten. A person’s goals and motivations change. The business landscape changes. You get to the end of the year, review the objectives and discover that none of the objectives that a person has are relevant anymore. The logical action when faced with this situation is to just ignore the objectives and review someone based upon feedback and your own personal viewpoint. Your team member gets the same performance score they did last year and then the whole cycle starts all over again.

In this situation you should think about the message that this is sending to your team member. You’re essentially saying “objectives aren’t really that important”. Don’t be surprised when you don’t get the buy-in next time objective setting comes around.

When companies are tied to yearly performance review cycles then early December and late January are the periods that managers hate. Believe me, it’s where you really get to be the bottleneck. There’ll be expectations from HR that you do all your reviews by a certain deadline. It’ll be the same deadline as all the other managers have. Everyone will be running around trying to do the same things. Free meeting rooms will be pounced on by the first person who sees free space in the calendar. Everywhere will be full of people in groups of two talking quietly.

Preparing for a performance review is extremely important and a manager can’t just rock up to one without having prepared. There’s a lot to be done. Feedback to be requested, notes to be collated, memory banks to be queried to remember what happened almost twelve month’s ago, feedback to be re-requested, notes to write, the review itself and subsequent follow-up. That’s just for one team member.

A yearly review cycle effectively takes the entire management population out of delivery work for two months a year. It creates bottlenecks. It’s one big performance management big bang. That’s not how we deliver software anymore.

It’s also disruptive for the team members. Suddenly everyone is being asked to provide feedback on everyone else, everyone is preparing for their own reviews at the same time and because those reviews only take place once a year then they take a long time to complete.

There is nothing more annoying than being told “well that thing you did 6 months ago – that wasn’t good”. You have no chance to change the situation and little chance to effectively learn from the feedback. The time will have past and the opportunity to change may well have gone as you’ve moved onto something new.

Yearly performance review cycles don’t of course preclude managers from giving regular feedback to their team members. But they do make it easier not to give that feedback, and not to seek it from others. They subtly encourage us to think that ‘proper’ feedback is only needed to be given once a year. That’s wrong.

When you do something regularly then it becomes easier. You learn how to do it, your brain becomes wired to do certain parts of the activity almost without thinking, and you lose your fear of something new. Mastering a new skill and gaining the confidence to do it well takes time and practice.

We don’t get to practice the art of performance reviews regularly in a yearly cycle. At best a manager may well have done about ten reviews a year for a couple of years at a company. Those reviews come round only once a year, by which time a lot of the skills are forgotten or take time to become natural again. You make mistakes, those mistakes de-motivate your team members and just as you feel like you’ve got your review mojo back, then it’s time to put it away again for another year.

This also applies to your team members. They get reviewed once per year. In fact it’s worse – they get fewer opportunities to get good at reviews than you do.

It’s human nature to fear change and to feel anxious and apprehensive about something that is new. A yearly performance cycle becomes something that neither manager nor team member looks forward to, precisely because it happens so infrequently that no-one get’s the chance to feel confident doing it.

When reviews are yearly then it you can find yourself trying to remember what both you and your team members were doing almost twelve months ago. Even with the best notes in the world, and the most fastidious team members, there will be points that are forgotten.

Feedback from other team members and stakeholders won’t focus on what was done in the past – when under pressure to provide feedback for multi people (which happens more under a yearly cycle) then people remember the recent past far better than something that happened months ago. And if they do remember something from months ago then it was probably an event they perceived as negative. Bad memories stick better than good ones. The feedback you get will come with an unintentional negative bias. Or it may not even be true at all.

I’m a strong believer is delivering software iteratively, seeking regular and timely feedback, and adapting as a result. In my career I’ve done this enough times to feel that this is the least risky way to deliver. We learn as we go along, and we change approach, feature set, timescales, etc when required.

One key metric I like for a team is lead time. How long does it take us, from the point at which we receive a request, to the point at which we deliver it? Enabling a suitably short lead time to enable the team to be nimble and adaptive is key to delivering valuable software. A yearly performance management cycle has a lead time of exactly that, one year. The opportunity to adapt is tiny.

I believe the traditional yearly performance review cycle does not work. It does not enable timely feedback, does not exploit our desire to work in the present, it’s time consuming and it’s demotivating for both team members and managers.

In my team we decided to do things differently. We changed how we do performance feedback and performance reviews. The next article in this series will tell you what we did, how we did it and what happened.

Having your team all working towards a common set of goals is extremely important. However, as leaders and managers we can sometimes get far too hung up on what needs to be delivered and forget about who is actually doing the work. Forgetting about the people and focusing only on delivery goals may get you to one particular deadline but failing to build the team effectively and align them around a common set of principles will rapidly cause longer term problems. A team charter can help prevent this.

At it’s heart a team wants to perform. People want to do good work; after all, feeling like one has not done the best one can possibly do is not a good feeling and as humans we naturally want to feel good. I like to sum this up like this:

Your team are a group of awesome people who want to deliver value. Your job as a manager is to enable them to do that.

So how can you help your team to bond around common goals, and ensure that these are not purely focused towards delivery or individual achievement? One way is by working with them to produce a team charter.

A team charter is a set of principles that the team live by. It should be produced by the team, owned by the team, and be visible to not only the team, but also all those who work with them. It defines who they are and how they like to work.

In short, it’s the team’s rules of the game.

When everyone understands the rules, were part of defining those rules and as a team they own those rules, then the team is stronger.

I recently organised and ran a workshop with my team in order to produce a charter. For some background, we consist of four different sub teams, each with around 6 people in them. The teams are cross functional software engineering teams, wth developers and testers, plus they have the skills and experience to push software live and build and maintain our infrastructure. In short they own our products from cradle to grave.

It was important first to set the scene and explain to the team what a charter is and why having one would be a good idea. A charter should be simple and so should how you explain one. Here’s how I explained charters to the team:

I thought it would help to give the team an example of a charter. I’d heard Stephanie Richardson-Dreyer talk at a tech meetup at MOO a few weeks beforehand and she gave me the idea for the charters, and had fortunately also written an excellent blog post on the subject based on experience from GDS. I recommend reading it – her team’s charter looked like this:

This was a great starting point and example for my team.

After some warm up ice-breakers then it was time to start thinking about what should go into our charter. While it could have been productive to jump straight to getting the team to think about what defines them as a team, previously I’ve found this is not always the easiest thing for them to do, and jumping straight to the solution doesn’t always get the best results. Sometimes trying something different helps people to think and come up with ideas more easily.

So I flipped their thinking around. Instead of thinking about what would define us as a team and what a good team would look like, I got them to think about the exact reverse.

Reversal is a popular problem solving technique and one that I’ve used on numerous occasions. I find it works for me. And sometimes, thinking about worse case scenarios can be fun. So the team were encouraged to think about the characteristics of unsuccessful teams then:

We then got the teams together and each team played-back their thoughts to the whole team. It was fun. We clearly knew what bad looked like 🙂

This is then where the reversal came into play – the teams were now encouraged to take their ideas (and any they had updated as a result of what they had heard from other teams) and note down the characteristics of successful teams instead. We encouraged them to think about their own context and the overall team, and how they wanted to work together and be recognised by stakeholders and other teams.

Once the teams had reversed their ideas we brought the ideas from each group together. A group discussion enabled us to find the commonality, discuss each theme and agree on importance. The result was a number of themes, one per post-it note, on the board. There were a lot of ideas.

Now it was the team’s turn to agree on what the most important items were to them. These would be the one’s that ended up on the charter. So another dot vote was called for. Each team member dot voted on their top 7 characteristics of our team.

We have our team charter. It looks something like this. It’s framed and on the wall for everyone to see. It defines us as a team to each other and to those we work with.

And when the time is right we’ll revisit it and update it if circumstances change.

I think so. The exercise of producing a charter brings team’s together and helps them bond around common goals and principles, and shows that the most important thing is the team. When new people join the team it helps them to understand what defines the team and what’s important. When new teams work with us then they can easily see what makes us tick.

Why not try a produce one with your team?

I found these two blog posts very useful when learning more about charters and preparing for the workshop with the team:

I really loved being a part of WeTest 2016. I gave the opening keynote at both conferences, as well as a couple of other talks at sponsor events. If you came to any of them then this post contains some useful links you may want to read. It was great to meet so many engaged and knowledgeable testers in New Zealand.

I was thrilled when I was offered the opportunity to travel over to New Zealand and talk at the WeTest 2016 conferences in Auckland and Wellington. I mentioned my conference speaking goal as part of my presentation at both events – this was that one day someone would invite me to speak in New Zealand. And Katrina Clokie, on behalf of WeTest did just that earlier in the year. It didn’t take long for me to agree to be a part of the conference and being offered the opening keynote was a real privilege.

Now there is one thing that’s clear and that is that it is a long way to New Zealand (28 hours to be precise from the UK). So I wanted to ensure that I made the most out of my short time there and to give a presentation that fitted in with the conference theme of “Influence and Inspire”. Given that I have made a move out of a pure test role over the last few years then this seemed like a logical theme for the presentation, and an opportunity for me to give my views, gained from outside of testing, on how testing is perceived. I also wanted to show the audiences that there’s important leadership roles within testing to be taken and made the most of.

I can say without a doubt that WeTest was the best organised conference that I have spoken at and it’s testament to the effort put in by Katrina, Aaron, Shirley and Dan. All too often presenters at conferences aren’t treated brilliantly by organisers – either by having a lack of support leading up to the event, being expected to pay their own way or by needing to foot the bill for travel and accommodation then claim back. WeTest was different – they organised and paid for all travel up front and sent detailed itineraries for each speaker, plans on how the conference rooms were to be setup, as well as ensuring that the simple things like a taxi to pick you up off a long haul flight was pre-arranged. It made the whole experience easy and it made us speakers feel valued. Other conferences should take note.

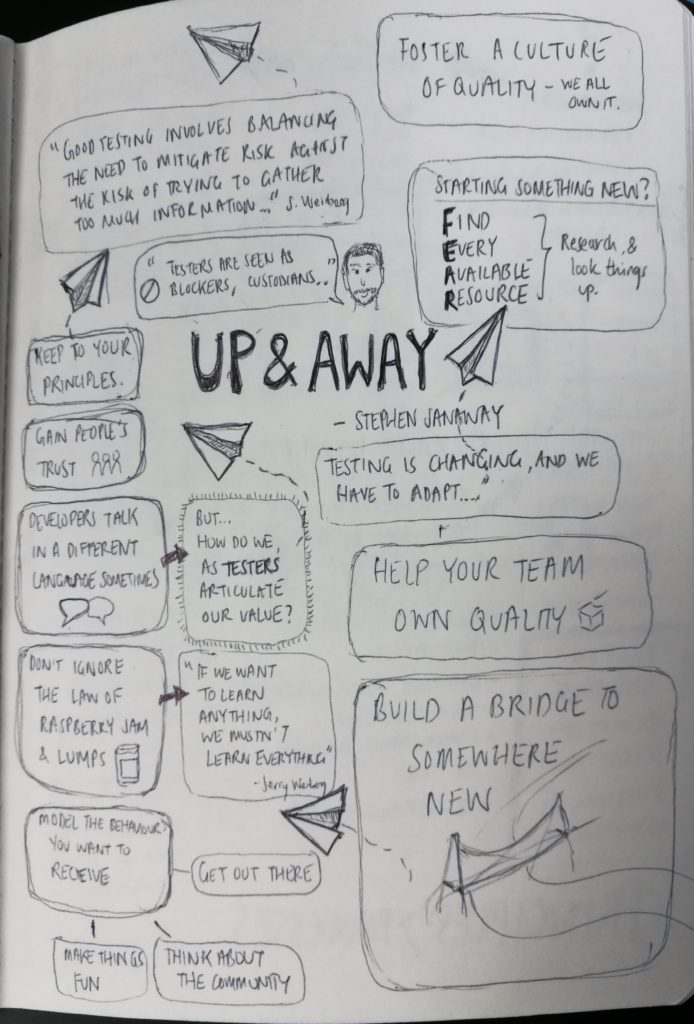

Up and Away?

My presentation focused on my views of testing from outside of just testing and how I made a move into software management and why. It was part of a clearly well thought out programme and the other presentations, whether focused on more technical aspects such as mobile testing, or other leadership presentation, fitted together really well. You can see the programme here to get a feel.

Highlights

I thought all the presentations were good but a particular highlight for me was Adam Howard’s “Exploratory Testing Live” where Adam took the really brave step of doing live exploratory testing on the Trade Me website in front of a conference audience. Fair to say it went a bit better in Wellington than Auckland, where he found a bug early on that blocked a lot of the rest of the session but he coped really well and there was value in both sessions. We don’t see enough live testing at testing conferences, it’s common to get live coding at development ones but hasn’t seemed to catch on. Based upon Adam’s session then it should.

Also I really enjoyed Joshua Raine’s really personal story about “Conservation of Spoons” which he did as a noslides presentation. Deeply personal at times and spell binding. I won’t give you the details because I’m sure he’ll do this one again and to know the story would spoil it.

As part of my presentation I thought I’d try out the new Q&A feature in Google Slides. It turned out that this was a good move because it enabled me to get questions from the audience as I talked and also to keep a record of all of them for later. If you speak at conferences I’d really recommend it.

For those of you who attended then here’s the questions asked, my responses, and a little more information.

I guess I miss being the expert with the safety of many years of experience of testing. I also make sure I keep connected to the testing community because it’s great and if I didn’t then that would be the biggest thing that I’d miss.

I make sure I do one thing well; that together with Jerry Weinberg’s Lump Law – “If we want to learn anything, we mustn’t try to learn everything” help me to maintain a balance. Trying to find the one thing to focus on is sometimes hard, but by discussing with your stakeholders and your team then you can usually come to find out what is the most important.

There’s not one clear answer to this – it depends on your context, languages and architecture that you are dealing with. When I started then I tended to use google a lot and base my searches on discussions I’d had with the dev’s in my team. I’d also ask them what they thought I should be learning and why. I’ve also found sites like Hacker News and Stack Overflow to be great for keeping up with what’s happening. Talking Code also comes recommended.

It was in the same company and I think it’s much easier to make a change from one path to another when you are in the same company. You have that reputation to use and you are a known quantity. It’s also likely that you’d been working towards such a change as part of your personal development anyway so the company will be confident in your plans.

I talked about how it can be scary to make changes but trying something new for 6 months is key. You need to understand that you will go through a change curve just like anyone else and things will feel extremely uncertain as a result at the beginning. I knew what to expect since I’ve been through other changes.

In this case I wasn’t specifically looking for change, more for an opportunity.

I like the idea of whole team testing and bug bashes are a great way of starting.

I think we’ll see less traditional testing roles and the focus on automated checking will become more of a development activity. This may mean that there are less testing roles in total but good, exploratory, coaching testers will always have a place in teams. I think the biggest change will affect Test Managers, with far less of a need for them and a transition to coaching roles.

Show that you have an interest to others in your company. Work with your manager to map out your path to a new role and start to show that you are learning the skills that will be required in order to be successful at it.

In short – you own the responsibility for your own career.

It does depend a lot on how the management structure adapts. In agile transitions that I have been a part of we’ve changed to autonomous, cross-functional teams with single managers, who have been supported by coaches for both agile, testing and development. This support network is key, as is the establishment of discipline based communities. A strong testing community for example, allows testers whose roles are changing to adapt.

I’ve spoken before about the effect of removing Test Managers from an organisation and the biggest takeaway for me was the need for a strong support network for testers afterwards.

Support from coaches allows not only testers to be supported but also means that someone with testing experience becomes responsible for establishing career paths, competency expectations, etc that can then be used by other managers who are not experienced in managing testers. It also helps maintain a ‘voice of testing’ towards senior management and to enable activities that help testers grow within an organisation.

The first conference was in Auckland and we repeated the experience again in Wellington three days afterwards. This meant that the whole WeTest circus upped sticks and set off for Wellington for a repeat performance. I also did an “Understand Your Mobile Users” presentation at a sponsor the night before, plus the same WeTest presentation at a sponsors internal conference the day afterwards. Four presentations in one week was something new to me and actually pretty interesting to do as I got into the speed of things. It almost felt like being in a band on tour 🙂

WeTest was great. I met some great people and learnt some new things. It was extremely well run by a passionate bunch of volunteers who knew how to treat their speakers well and how to organise a great programme for the conferences. The testing community in New Zealand is really engaged and it’s clear that there’s some really forward looking testers pushing the boundaries here. If you get yourself over to New Zealand then I’d certainly recommend it. It’s not that far. Really 🙂

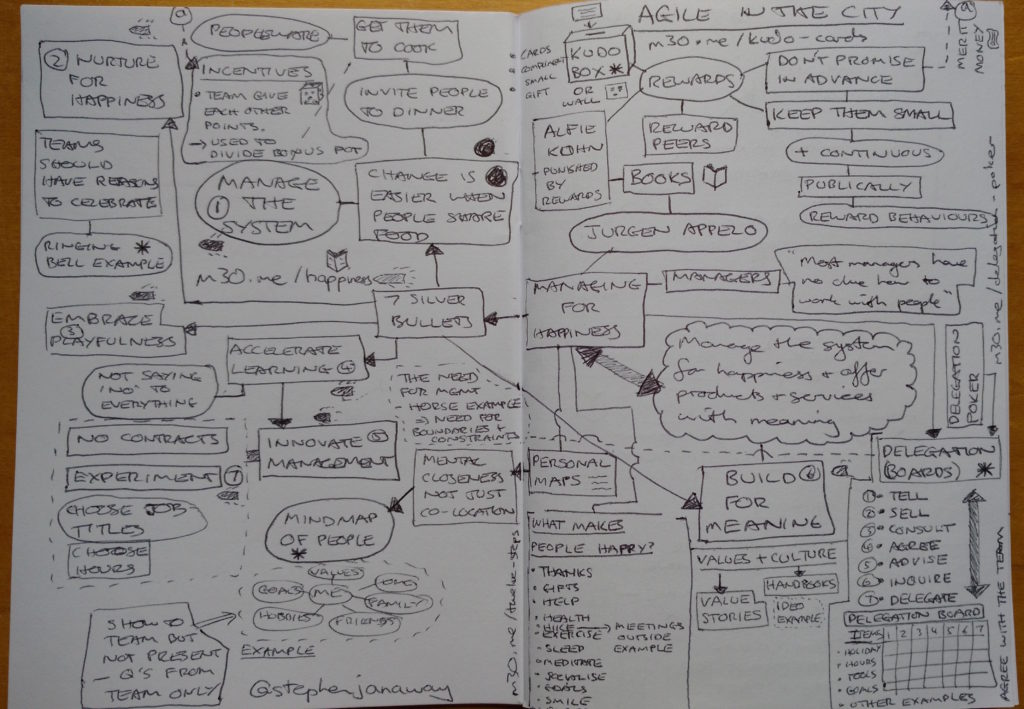

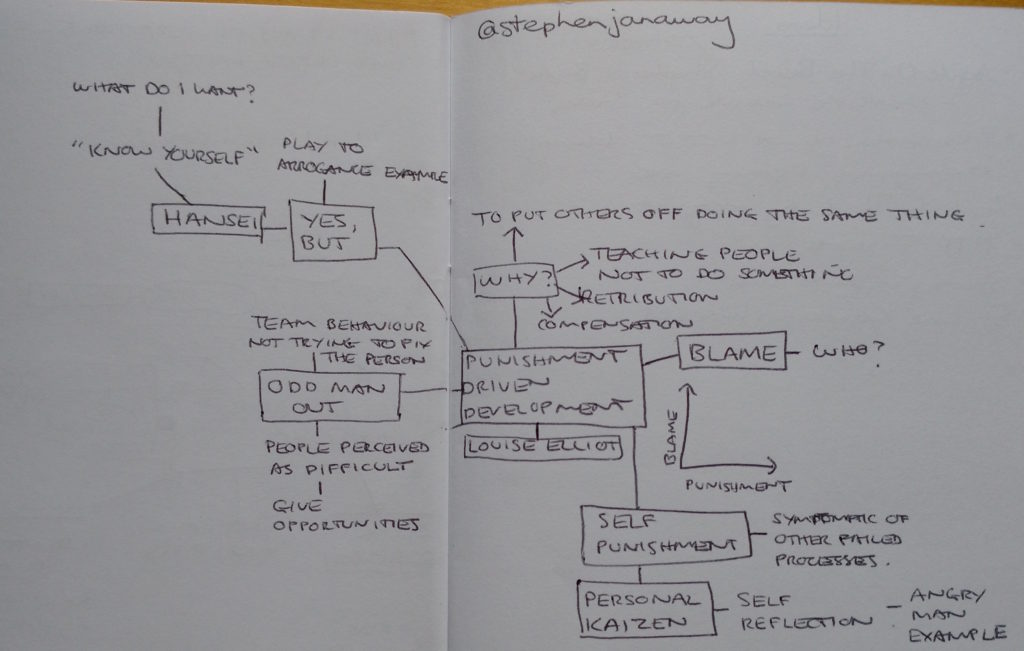

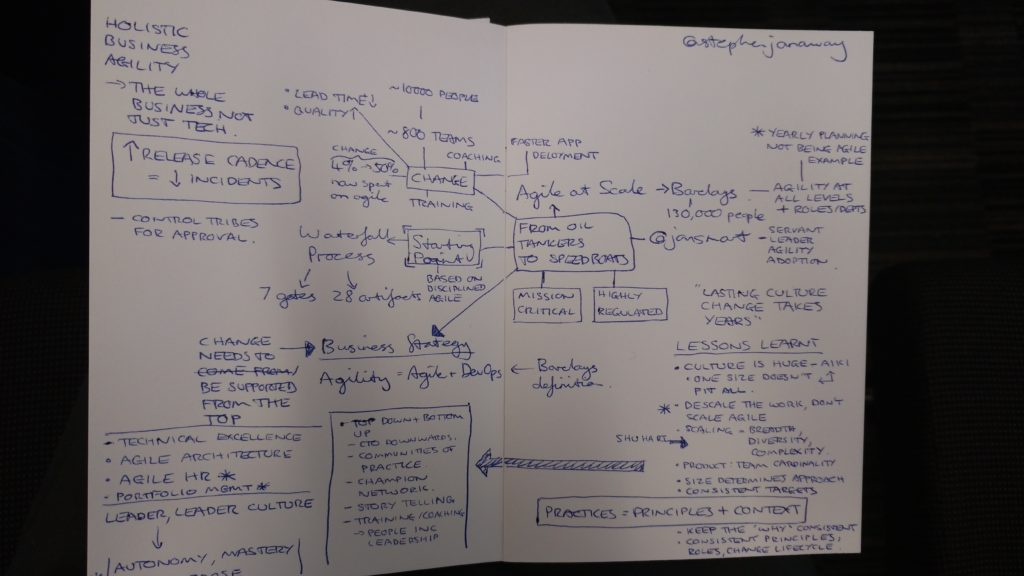

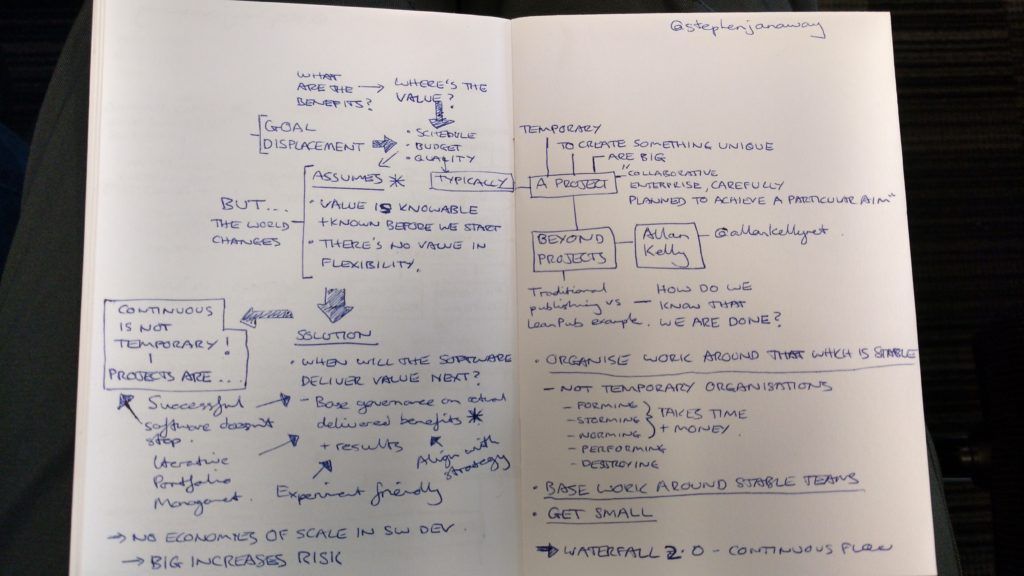

I’ve just got back from Agile In The City, which is a relatively new agile conference held in London. It’s in its second year and this was the first time it had been extended to two days. I had a great time; there was a good mix of talks, tutorials and workshops, a decent venue and even some good food as well.

As usual I did some mind maps of the sessions I attended. My favourite session was Managing For Happiness from Jurgen Appelo, a really inspiring keynote about how to manage better, with some great tips.

My mind maps from all the sessions I attended are below.

Develop The Product Not The Software – David Leach (with free water pistol 🙂

I’ve been reading a lot about test management recently. There’s some excellent posts out there, in particular I’d recommend you look at this one from Katrina Clokie, explaining the changes that are required for test management to remain relevant in the world of Agile software development and continuous delivery.

She also links some other articles which I would definitely recommend you read, if you are interested in the subject.

So why am I interested? Well for starter I’m a Test Manager. Over the last couple of years I have seen my role change, from one of leading a separate, large test department, to one of managing testers across a number of project teams. It’s about to change again.

I’ve seen the challenges being a Test Manager in an Agile environment brings, in particular the difficulty in remaining relevant in the eyes of product and development managers, and the challenges of understanding enough about multiple areas in order to be able to support your team members. Being a Test Manager in a Agile environment can be isolating at times, particularly when the department is big, and the number of agile teams is large. It requires an ability to balance a lot of information, priorities, and tasks, across a number of areas. Stakeholder management and influence become key. Context switching comes as standard. Often it’s not much fun.

Through discussions with others, and looking at my own situation, I’m increasingly coming to the conclusion that the new ‘Agile Test Manager’ positions that Test Managers are moving/ falling into just don’t fit with the ways that teams want to work anymore. The team is more important than the manager, and, for example, choosing to keep discipline based management because it means testers are managed by testing ‘experts’ isn’t enough to justify it. Managers are not able to effectively support their people if they do not have the time and energy to keep fully in the loop with the team. As Test Managers get split across multiple teams, (primarily because having one Test Manager per Agile team is massive waste), then it becomes nearly impossible.

Moving to Continuous Delivery complicates matters further. Giving a team complete autonomy to design, build and release it’s own code is an extremely motivating way of working. Do Test Managers fit in with this ? I’m not sure they do. Where independence and autonomy are key, management from someone from outside of the team just doesn’t fit, particularly when that management is only part-time.

So how do we change? Do Test Managers merely become people managers, desperately trying to understand what their people, spread across multiple teams, are up to? Are they there to help manage testing but not people?? What about the coaching and mentoring, the sharing of knowledge and expertise, and the personal development of testers?

As I see it I think we’re going to see a lot more of this sort of setup:

The dedicated Test Manager, who manages testers and testing is not a role I can see continuing for too much longer. It is a hangover from the past, when large, dedicated test teams needed management, and it simply does not fit with how a lot of teams work anymore.

But, and this is a big but, I work in web, web services and mobile. I’ve seen the push for Agile and the push for Continuous Delivery because it fits the nature of the projects and technology used in these areas. Team’s are lean and projects are short. Almost certainly this makes me biased.

I would be interested to know what you think. Do you think the traditional Test Management role is reaching the end of the road? Or is it alive and well, and relevant in the area that you work? Why not leave a comment below and get the conversation started.

I firmly believe that in order to be as effective as possible, testers need to engage with the software testing community. Learning from others, particularly outside of the companies where we work, makes us more rounded and better informed individuals. It enables us to inspire ourselves and our colleagues in ways that we could not otherwise.

Recently I’ve been wondering why more people do not engage with the community. What is stopping them, and how can we all help change this? We can explain how brilliant the wider community is, and we can give examples from our experience. We can send people to conferences and email round blog posts. What is that does not work?

What do we do about those within a team who do not want to interact? Those who do not see it as a good use of their time, and are not willing to spend time on community matters, even if that time is given to them by the company. Should we incentivise people to do so? At least in order to push them in the direction of the wider testing community, where hopefully they will get hooked? Or should we do the opposite? Is it a valid idea to make community engagement a part of people’s role description, and therefore penalise those who hold such positions and do not exhibit such engagement?

Or is there another way of persuading everyone that the software testing community is key to their personal development? I’d be interested to know what you think.